The action: When asking for input from your team on major decisions, don’t be afraid to show your thinking and talk about potential down-sides. It builds trust and gets you more valuable feedback.

The long-form:

Two types of false inclusion

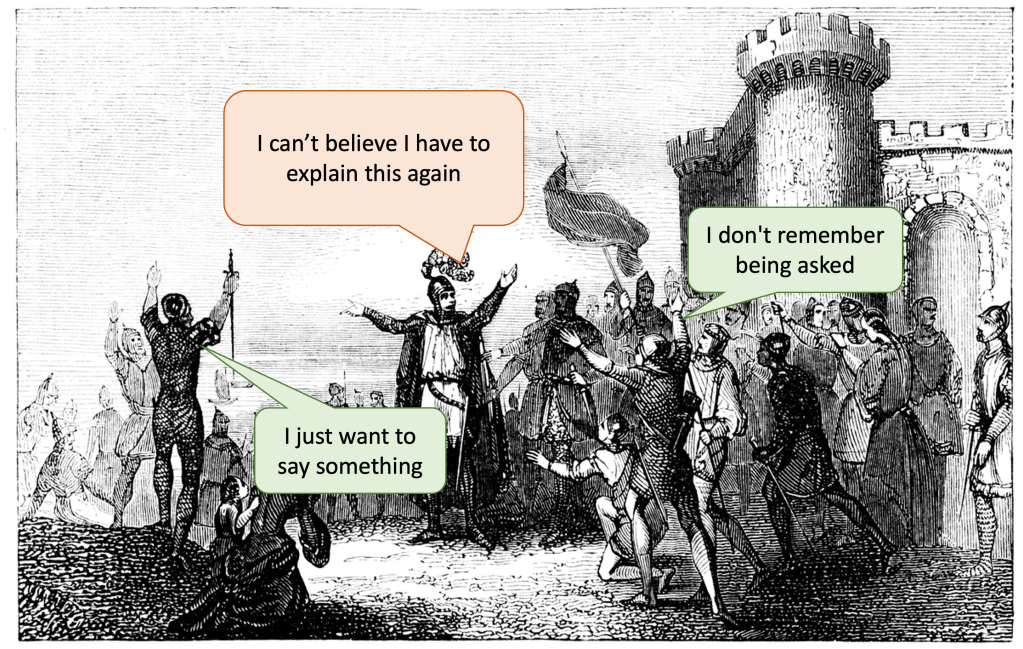

“We want to include you in the strategy process,” you read on the company-wide posters. Management has decided to revamp the company strategy, but this time “it’s going to be a fully aligned and inclusive process.” In most companies that means one of two things:

Either you are brought in to a town hall meeting where a C-suite member explains what the new strategy will be. “We have decided to focus on the major cities. The reason is shown in these compelling graphs.” Perhaps you’re asked to give input, but as you watch Carol from Marketing get ridiculed from the stage for her critical comment, you all agree it’s better to sit tight.

You feel like your input was less than wanted, yet on the other side management feels like they made a valiant effort at including, but the organisation had nothing to offer.

Or you are gathered in smaller groups and presented with a much too broad question. “What do you think our strategy should be?”

Of course, you have no idea what the scope and prerequisites of that question are, so you fumble a vague and irrelevant answer.

Again, management has made an attempt to include the rest of the organisation, but you have been found lacking in sophistication and strategic thinking.

A better way: A draft, clarifying questions and feedback

The point is that asking for — and giving — input is hard. You need to be clear on what you are asking people to do, specific on how they can contribute, and upfront about how the final decision will be made.

In the first example above, no-one knew what they were expected to do. In the words of the DARE-decision rules, were they asked to give advice on the proposal, recommend alternatives, execute the plan, or even decide on the strategy?

In the second example, management asked people with limited time and context to recommend a strategy — which clearly needs more work than people are able to give in a single sitting. Also: Creating something out of nothing is much harder than reacting to a proposal. It should therefore be management’s responsibility to create the first draft for others to react to.

In the Four Disciplines of Execution (McChesney, Covey, Huling), the authors detail a better way to include the organisation in major decisions. The book’s use-case is for “Wildly Important Goals,” but it could be used for anything you need input on, such as strategy:

- Management comes up with a draft strategy. And this really is a draft until the organisation has given input.

- Invite the rest of the organisation to provide their feedback. But first: Be totally clear up front on what the roles in the following discussion are:

- The top management team will make the final decision

- The levels below are there to gain understanding as well as offer their insights. Their views are essential to the quality of the final decision, but they are not there to be sold on the final decision, engage in endless debate nor have a vote. People have to have their say, but they don’t have to have their way.

- Share the logic of how you got to these decisions:

- Walk people through your thinking, so that people can see the assumptions on which this proposal rests (and identify which ones may be wrong)

- Outline which other options were considered and rejected. Why were they not deemed the best alternative?

- Speak candidly of where the proposed plan has faults. Not only does this ask your team for help in finding solutions, it also shows respect for their intelligence and experience.

- Split people into smaller groups and ask them to write down clarifying questions about the chosen alternative. This is not feedback yet, just what needs to be clarified to reduce misunderstandings in the next step.

- In the same groups, write down feedback you have for the chosen alternative. It is not a debate, but it is vital that the top management team hears and understands the criticism from their teams.

- Make the final decision. Incorporate relevant feedback, but also acknowledge which critical comments were rejected and why.

When people are heard and included in a useful way you not only get faster execution, but also better plans. The best sources of information in a company are usually on the front lines, close to the customer, employee or competitor. By providing a better process for including their input you’ll find the quality of your plans quickly improving.

See also: