The action: Make sure you have a mix of short-term projects, and long-term, less certain, strategic projects.

The problem: You’re at your company’s annual strategy workshop, and the team just can’t agree. One member of the group feels that you don’t need a new strategy since everything is going quite well. Another thinks the strategy should be to increase prices on a few products. And John from HR has just read up on Google’s moonshots and is not leaving until you all come up with a wild plan to forever change the face of your industry.

In short, none of you can agree on what time frame you should be looking at. And how ambitious should a strategy be? Is doing nothing fine, or do we always need wild moonshots?

The long-form: We like to think of strategy as a set of bold decisions by visionary leaders. Yet, very few companies end up where they are solely due to dramatic shifts. Most of the companies around us are the results of years of adaptation, minor projects, and incremental changes. However, there are times when more drastic and ambitious changes are called for. But how do you know when that time comes?

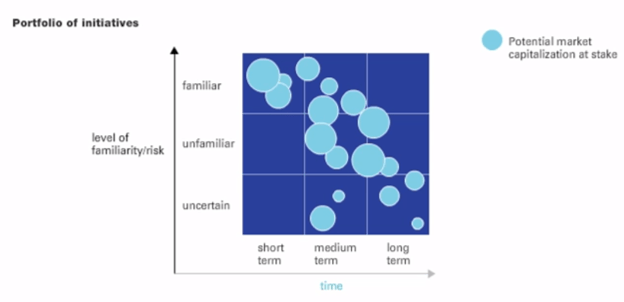

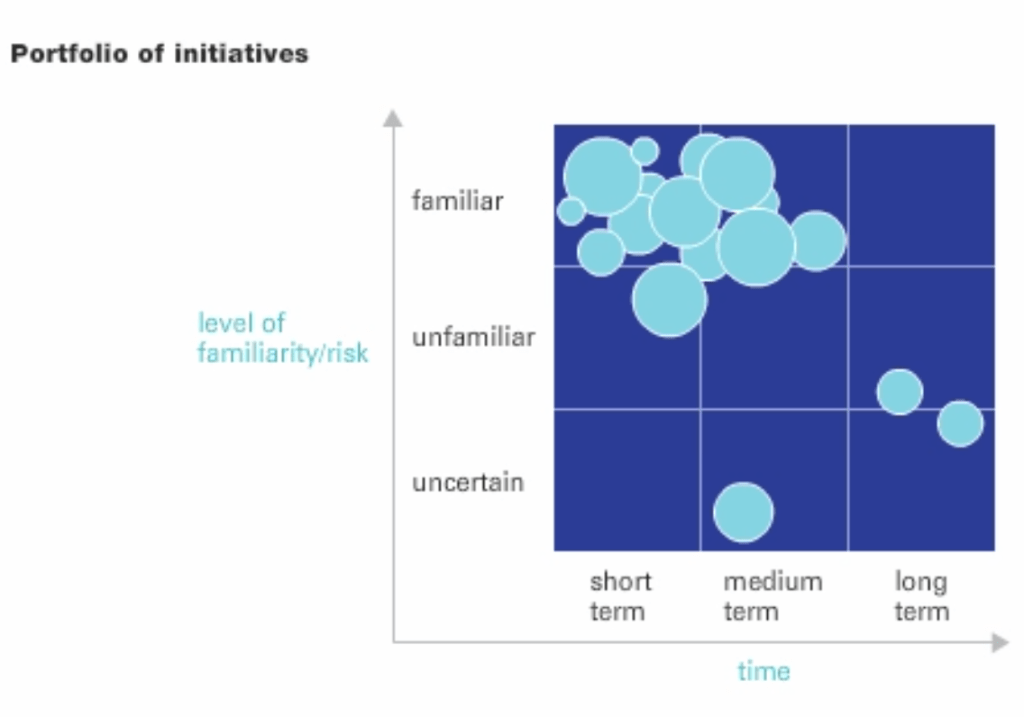

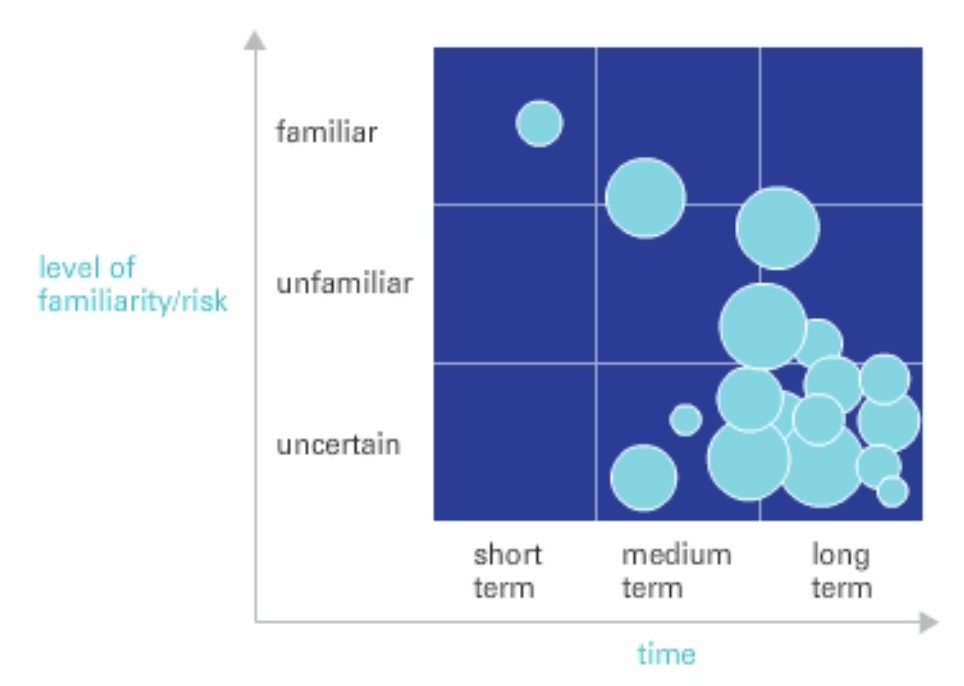

The Portfolio of Initiatives-framework by Lowell Bryan of McKinsey can be a useful way to sort out these discussions. By mapping all the planned initiatives (projects, strategic plans or actions) on a graph you can match them to two factors: Time and familiarity.

Familiarity: On the vertical axis, you map how familiar this project or goal is to what you are already doing. In other words, how confident are you that it will be successful? If you have the talent, knowledge, and reputation to get the desired results, your level of familiarity is high.

On the other hand, moving into new markets or creating products very different from those you make today suggests a low level of familiarity – and thus a higher level of risk. Taking unfamiliar action typically requires more investment in time and money, and move you further away from your current area of expertise. But moving into the unknown can also be where the largest prizes are to be won. Think of Apple’s invention of the iPhone or NASA’s mission to the moon.

Time: On the horizontal axis, we map when we start to see results – often in the form of recurring earnings from the project. Is it within the next year or so (short term), in two to five years, or longer?

Balance: Looking at the entire portfolio of initiatives you want to strike a balance between the time horizons. You need a healthy size of short term earnings where you are most familiar (upper-left corner, your current core business), such as the pricing changes mentioned in the introduction. But if all your projects are here, you may find yourself in trouble in a few years when the competitors’ products have improved or the market has moved on. You’ve won some battles, but lost the war.

And on the other hand, if all you have are risky moonshots, you will have tied up too much resources in exploration, without the supporting earnings from exploiting opportunities closer to home.

Ideally your portfolio of initiatives should look like a diagonal line, pointing down to the right with a fair distribution of projects ranging from familiarity to ambitiously uncertain and long term.

So for your next strategy meeting, try to be explicit on which time-frame are we currently discussing and what is our confidence that we will get the results needed. Group all the suggested initiatives according to time horizon, discuss which to focus on within each time frame, and keep the number manageable (see f40: Agree on the 1-3 most important goals).